In New Zealand, the spring months are September to November, the summer months are December to February, the autumn is March to May, and the winter is June to August. Therefore, the Kiwis (New Zealanders) often sail north to Fiji or Tonga in May, and the sailors wishing to visit New Zealand sail south in October-November.

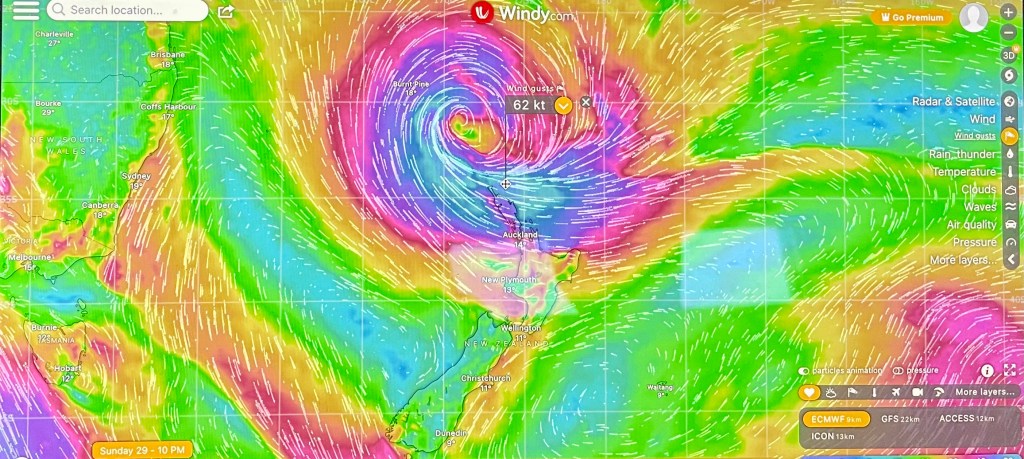

The insurance companies want their boats out of Fiji by November, the official start of the tropical cyclone (hurricane) season at mid-latitudes. This year, the weather phenomenon called El Niño started early and strongly with much more elevated sea temperatures than expected. It is known that a sea temperature of over 26-27*C triggers hurricanes and cyclones. For this reason, we decided to leave Fiji in early October with the first “weather window.”

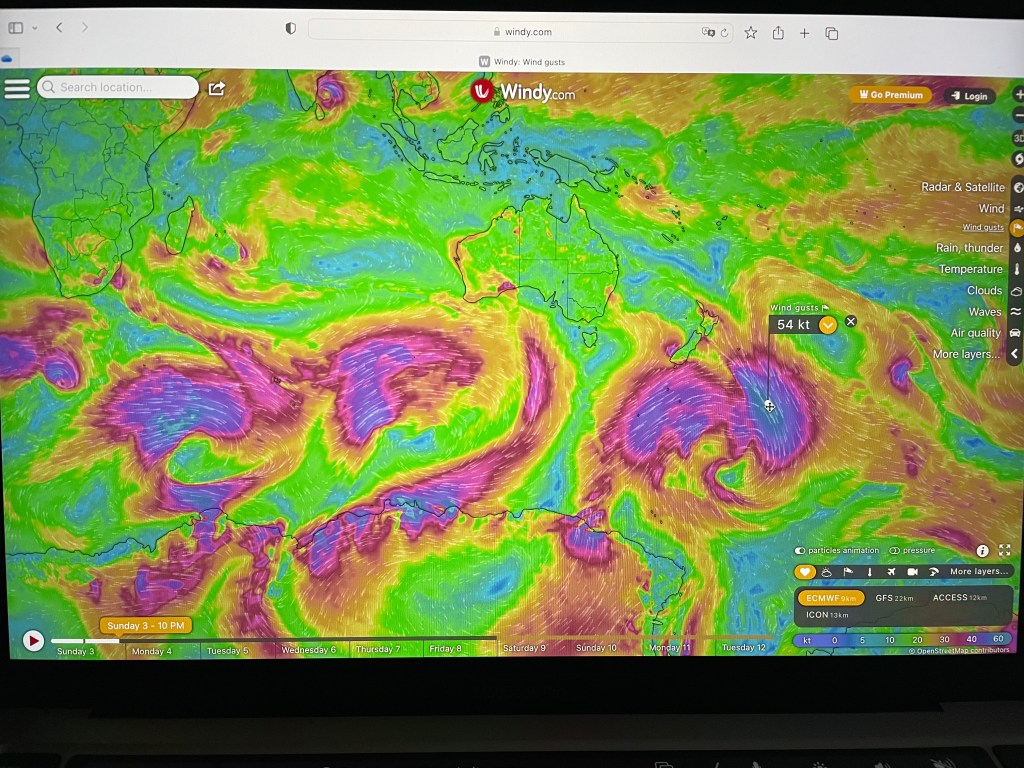

At this time of the year, at the latitude of New Zealand, the weather pattern is characterized by a seemingly “never-ending” procession of eastwardly moving low-pressure systems, often powerful, alternating with high-pressure systems. Contrary to the Northern Hemisphere, the low-pressure systems rotate in a clockwise fashion around the center, and the high-pressure systems in a counterclockwise fashion. The low-pressure systems rotate north of Antartica and bring cold polar air.

Timing the passage in a proper weather window is essential for an uneventful and comfortable passage. Statistically, the best weather window is when, in the bight of Australia, a high-pressure system is forming with a pressure of 1015-1025 mb in the center. A pressure higher than that is not good because it will trigger very strong trade winds (Easterlies) around and south of Fiji, which will make the first few days of the passage very uncomfortable.

It is also important to time the passage with the next low-pressure system arriving north of New Zealand because that will determine the strength of the westerlies. In between the easterlies and the westerlies, there is often a windless area called, in the past, “horse latitudes” because, before the invention of mechanical propulsion, sailing ships used to be stuck there for days waiting for a reasonable breeze. When the fresh water supply started to become scarce, they threw the horses overboard.

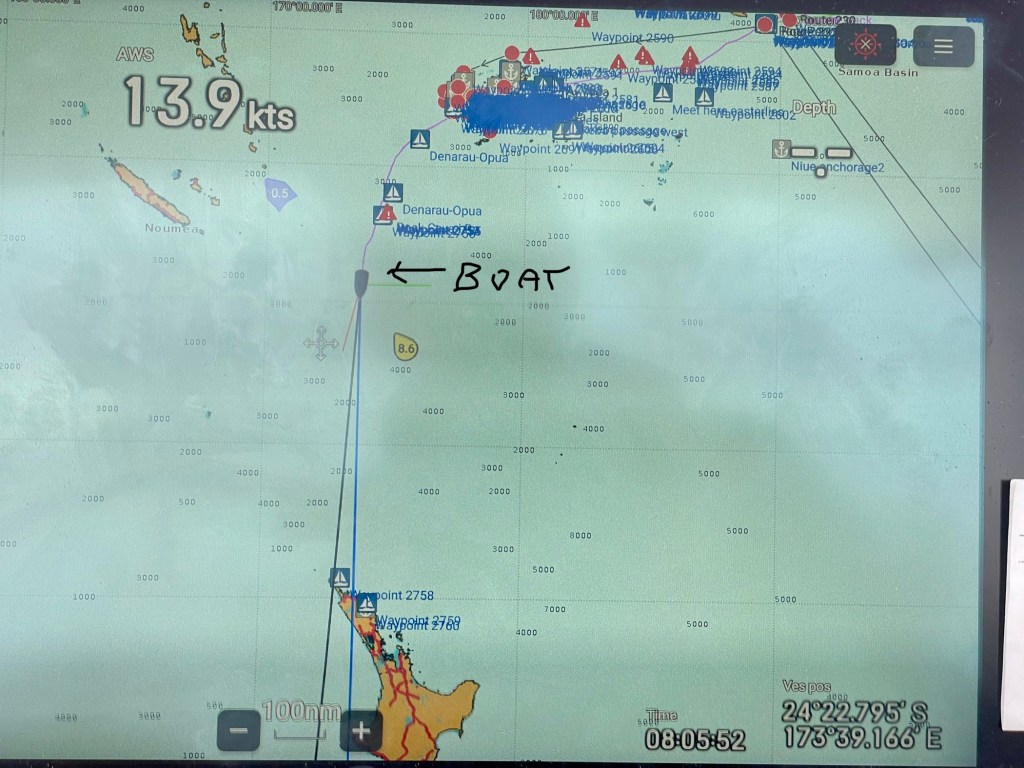

Ideally, going south, you leave on port tack with the wind abeam; you head southwest toward Norfolk Island near the coordinates of 29*S and 168*E, and, if you are lucky, you avoid the “horse latitudes” that are variable in location and width. Then, you change to starboard tack when the westerlies fill in.

It is essential to optimize the speed of the boat to avoid the next low-pressure system arriving north of New Zealand. If necessary, you can always slow down.

We took advantage of the weather guru Bruce Buckley from Australia, who helped us find the best weather window for our departure. We left Denerau, Fiji, on October 9, 2023, heading southwest. We expected strong winds for the first day or so.

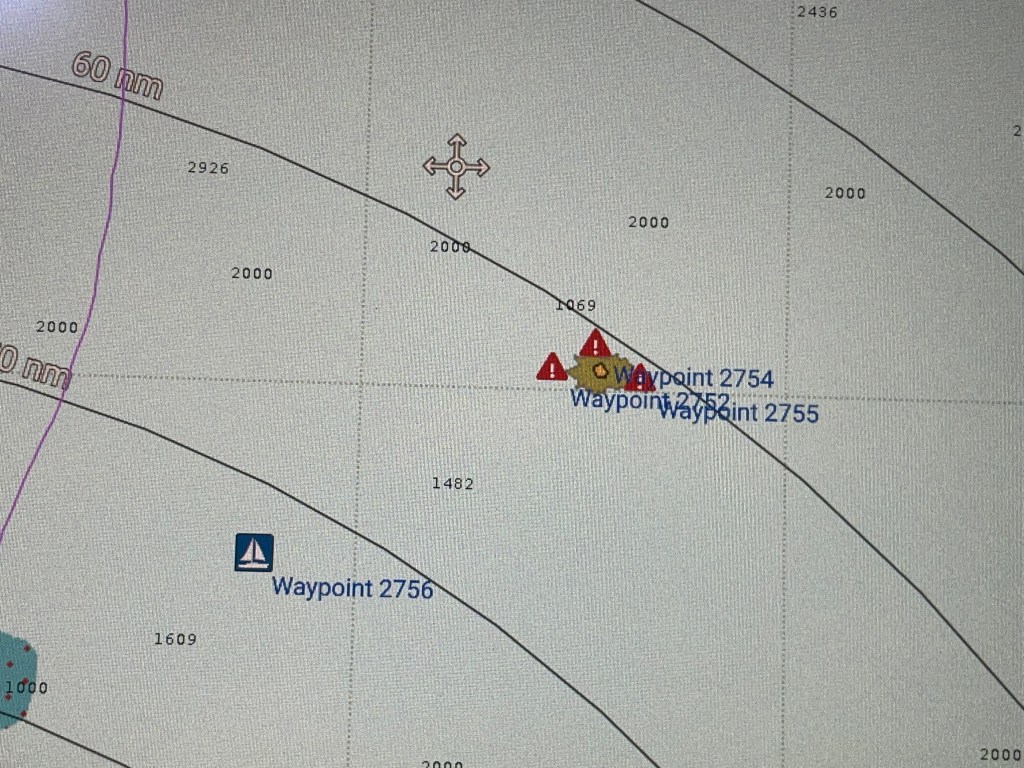

During her shift in the cockpit, Jan noticed that several miles south of us there was a small island-a 2 meter tall rock- located 21*44.41S and 174*38.38E. This rock, called Neva-I-Ra, is not visible at low definition on the electronic map of the chart-plotter, and becomes visible only at high definition: zoomed-in. All around the depth is 1,500-2,000 meters. It is basically the very top of a ~2,000 meter tall mountain.

Unfortunately, we could not avoid the “horse latitudes” and had to motor for about 30 hours to keep a satisfactory speed. Then, finally, the westerlies filled in and we were able to go faster without using the engine.

After seven days and ~1,118 NM, we reached the North Cape. During the last three days, the temperature had decreased considerably due to the arrival of the polar westerlies.

Jan, I’m so glad you saw th

LikeLike